In the Middle Ages, the site of the present-day Klagesmarkt – by the Steintor [now a pedestrian precinct] and the city walls of Hanover – was used for public executions. Later on, it took on its historical role as a trading venue, a tradition that continues to this day: it hosted one of the largest horse fairs in Europe and, since the 19th century, a market for pottery and porcelain (“Pöttemarkt”), and a daily fruit and vegetable market.

A place for parades

However, this spacious public area was not just a marketplace. With the editorial office and printing press of the Social Democratic newspaper “Volkswille” [“Will of the People”] just a few metres away in the trade union building and the party building of the Communist Party of Germany [Kommunistische Partei Deutschlands, abbreviated to KPD] at Klagesmarkt 21, the square traditionally served as a venue for rallies and as a starting point for parades of the workers’ movement.

Protest against Hitler

On 31 January 1933, one day after Hitler was appointed Reichskanzler, 3000 communists gathered here to protest and then proceeded to march through the city. February 19, 1933, became a symbolic day. Not long before, a National Socialist had been appointed Chief of Police in Hanover. On this day the new rulers showed their strength: uniformed troops of the SS [the abbreviation of “Schutzstaffel”, “Protection Squadron”], the SA [the abbreviation of ‘Sturmabteilung’, literally ‘Storm Detachment’, the Nazis’ paramilitary wing, known as ‘Brownshirts’] and Hitler Youth marched for the first time from Klagesmarkt and over the Ihme Bridge to marching music and through “red Linden”, in other words socialist Linden. That afternoon, a counter-rally by 45,000 supporters of the Republic took place at the same location: “Show the reactionaries that Hanover is staying red”, were the defiant words on the SPD leaflets. Around 30,000 demonstrators then marched through the middle-class Südstadt.

“Brown” [Nazi] terror

Two days later, two Social Democrats were ambushed and shot dead by SA men at the “Lister Turm” [Lister Tower]; ten days later Hanover’s SPD newspaper “Vorwärts” [“Forwards”] was published for the last time. The KPD’s newspaper “Neue Arbeiter Zeitung” [“New Worker’s Newspaper”], printed in a rear building on Klagesmarkt, had already been banned. After the burning of the Berlin Reichstag on 27 February, mass arrests also took place in Hanover and on 1 April the trade union buildings were occupied. Except for a few pockets of illegal resistance, “red Hanover” was a thing of the past.

“Judenfrei”: “Free of Jews”

The boycott campaigns against Jewish businesses, which started on 1 April 1933, also had an impact on the Klagesmarkt: at the end of June 1933, a decision by the city magistrates excluded all Jewish traders from the city’s markets and funfairs; they became – in the words of the regime – “judenfrei”. And the violence continued. In September 1941, a privately owned Jewish house situated on the corner of Klagesmarkt and Otto-Brenner-Strasse (then known as Josephstrasse) was forcibly turned into one of Hanover’s 15 “Judenhäuser”, i.e. “Jewish houses”. Around 80 people were forced to live here.

This “Jewish house” too was located near the city centre and was a favourite target of night-time raids. In court trials that took place after the war against Hanover’s Gestapo officials, it was repeatedly cited as a site of the most brutal incidents of mistreatment. The majority of the coerced residents were already transported to their deaths on the first deportation to Riga in December 1941.

Underground bunker beneath the square

The boycott campaigns against Jewish businesses, which started on 1 April 1933, also had an impact on the Klagesmarkt: at the end of June 1933, a decision by the city magistrates excluded all Jewish traders from the city’s markets and funfairs; they became – in the words of the regime – “judenfrei”. And the violence continued. In September 1941, a privately owned Jewish house situated on the corner of Klagesmarkt and Otto-Brenner-Strasse (then known as Josephstrasse) was forcibly turned into one of Hanover’s 15 “Judenhäuser”, i.e. “Jewish houses”. Around 80 people were forced to live here.

Unlike the surrounding residential buildings, the bunker survived the war undamaged. However, at the sound of air raid sirens, terrible scenes played out before its entrances. In the panic, people seeking shelter were injured or trampled to death – in July 1944 alone, most likely 28 people died on the steps going down to the doors to the bunker, including six children.

Faced with the housing shortage in the post-war period, opportunities for using the building for other purposes were quickly found. From the time of the first export fair in Hannover-Laatzen in 1947, the city leased out the bunker to a tenant who ran an underground hotel here – at least until 1963. The bunker then stood empty, but after the construction of the Berlin Wall in 1961 and the Cuban Missile Crisis in 1962, it was inspected for its potential to be reused as a nuclear bunker. Fortunately, nothing came of it. Life soon returned to the concrete colossus when, under the direction of the “flea market director” Reinhard Schamuhn [who organised the first flea-market in Germany], the “Kunst-Center Hannover” [Hanover Art Centre] opened. It ran from 1969 to 1973 and featured studios, practice rooms for musicians, a theatre stage and a tea room.

A central meeting place on 1 May

With the opening of the market halls on the Tönniesberg in the 1950s, the Klagesmarkt had lost its traditional function as a wholesale market. All that remained was a weekly market on the northern part opposite Christuskirche and occasional pottery and porcelain markets and funfairs on the southern part, an area which otherwise served as a drab car park. Nevertheless, this large, open space near the city centre still retained its function as a venue for parades and demonstrations. On 31 March 1979, the largest anti-nuclear demonstration up to then and still the largest demonstration in Lower Saxony took place here attended by around 100,000 people – the final rally of the Gorleben trek that had started a week earlier in the Wendland region with around 500 tractors.

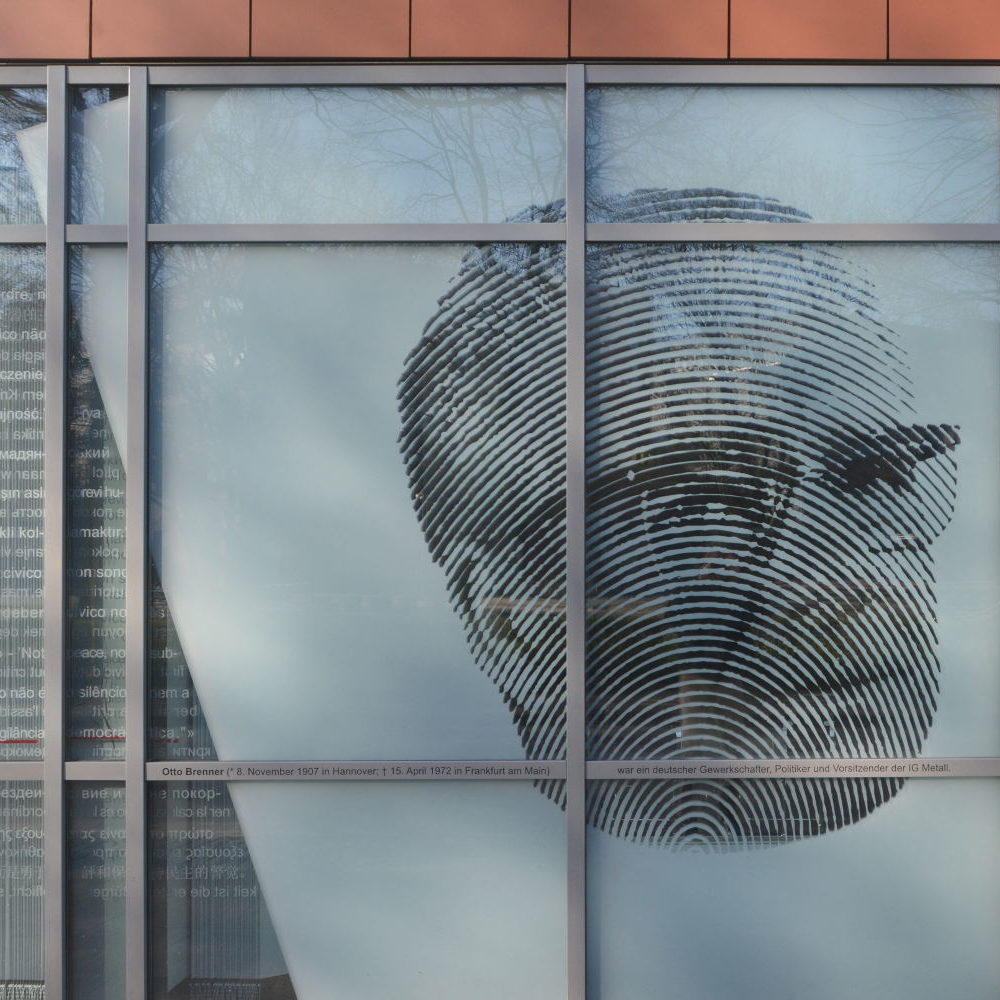

As early as 1953, the multi-storey building of the German Trade Union Confederation [Deutscher Gewerkschaftsbund, abbreviated to DGB] was inaugurated at the southern end of the square, on what is now Otto-Brenner-Strasse. For decades, local demonstration marches met at the foot of the building on Klagesmarkt for “Labour Day” on 1 May. The May Day festival on Klagesmarkt was an institution featuring speeches, music stages, beer tents and stands organised by civil society initiatives.

This came to an end in 2013 when the May Day Festival had to move to Trammplatz in front of the Neues Rathaus [New City Hall]. Following an urban development competition, an underground car park was built on the former parking lot in 2014-2016, with several residential and commercial buildings on top. Before it was constructed this, the air raid shelter was demolished. As a consolation and reminder of the square that once existed here, a city plaque has since provided information about its history through text and pictures.

Additional online information

Culture of Remembrance Downloadable information and memorial panels [in German]

Wikipedia entry Klagesmarkt [in German]

Stefan Kleinschmidt A brief history of the underground bunker beneath Klagesmarkt 1940 to 2013 [in German] (PDF)

IG Metall Hannover Working for peace in Hanover [in German]

Further reading: Click here

Texts and images: Michael Pechel

![Hanover: Call to the rally of the Iron Front [organisation of social democrats, trade unionists and liberals, which aimed to defend liberal democracy against the far-right and far-left, closely associated with the SPD] to defend the Republic on 19 February 1933. Clipping taken from the election campaign newspaper issued by the Hanover SPD for the Reichstag elections on 5 March 1933, "Das Signal", issue no.1/1933 dated 15 February 1933. Historical Museum of Hanover](https://zukunft-heisst-erinnern.de/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/klagesmarkt_3-1000x1000.jpg)

![Hanover: Last rally of the “Black, Red, Gold Banner of the Reich” [organisation set up in 1924 by the SPD, the German Centre Party, and the (liberal) German Democratic Party to defend parliamentary democracy] at Klagesmarkt, 26 February 1933. In the background is Postkamp. Archive of Social Democracy / Friedrich Ebert Foundation](https://zukunft-heisst-erinnern.de/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/klagesmarkt_4-1000x1000.jpeg)