Special Courts, including the Special Court in Hanover, evolved over the 12 years of National Socialist rule from being special criminal tribunals dedicated to the persecution of the Nazi’s political opponents to “armoured troops of the criminal justice system”, there to keep the entire (wartime) society submissive by doling out draconian threats of punishment.

Legal system protects the Nazi regime

On 21 March 1933, directly after the National Socialists come to power, additional special courts are established in each of the higher regional court districts existing at that time. During the transition to total rule, their main purpose was to persecute Social Democrats and Communists, and to hear criminal cases listed in the “Reichstag Fire Decree” of 28 February 1933 and the “Perfidy Decree” of 21 March 1933. A common feature is the indefinite suspension of fundamental rights (such as freedom of the press, freedom of assembly, protection of the home and so on) and the curtailment of the rights of defendants in court. Hence, the state of emergency becomes indefinite. Special courts are created literally to get cases over and done with quickly; there is no right of appeal against their decisions.

Once it has established its position, the regime extends the remit of the special courts to include punishment of all opinions critical of the party and the state – all it takes is a ribald joke. Cases of organised political resistance (“high treason”) are dealt with by the People’s Court in Berlin or special criminal divisions, for example, the trials of members of the Hanover Socialist Front following the waves of arrests in 1935-37 are brought before the Higher Regional Court in Hamm, which has the relevant jurisdiction. After the start of the war, the special courts punish any infringement of the newly declared decrees, such as the Decree on Antisocial Parasites or the Broadcasting Decree, by imposing draconian sentences: they were in effect “summary court martials on the home front”

Hanover Special Court

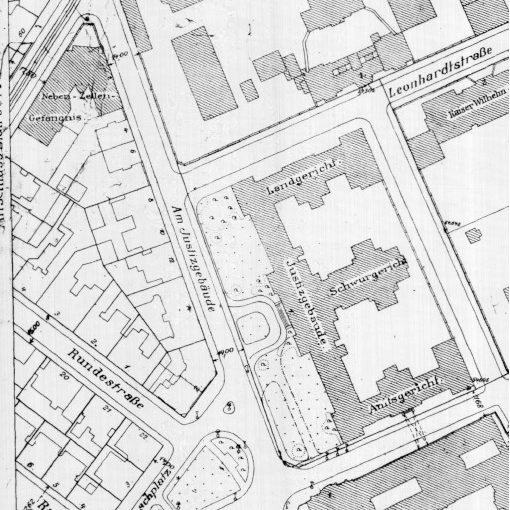

The special court for the area under the jurisdiction of the Celle Higher Regional Court is responsible for the region that is now the state of Lower Saxony (excluding the states of Oldenburg and Braunschweig, which at that time were independent). It is located at the Hanover Regional Court in the “Old Justice Building” on Raschplatz, which has been used since 1882; after it is destroyed in 1943, it operates from the “New Justice Building” on Volgersweg, the site of the present-day district court [Amtsgericht]. However, in the later stages of the war, the special court operates a “mobile court”, which also passes verdicts in locations outside of Hanover. Between 1933 and 1945, this conducts an estimated 4,200 trials leading to prosecutions, with the majority taking place during the war. Also, the number of death sentences handed down reaches a peak in 1943 with a figure of 59.

Before the start of the war, cases punished under the “Reichstag Fire Decree” and “Perfidy Decree” predominate. And it is not always the political left that is targeted. From 1936 onwards, the transition to overt military rearmament leads to an increase in the number of prosecutions against members of the Jehovah’s Witnesses (“International Bible Students Association”) for violating the ban on the organisation and its activities, which was enacted in June 1933. This is because “Jehovah’s Witnesses” resolutely and with great courage refuse not only military service, but also to build barracks or to work in the armaments industry. In the first half of 1937, the special court in Hanover hands down prison sentences of up to two years each against a total of 98 members of the “Jehovah’s Witnesses”.

Thought-crime

The actual muzzle paragraphs, however, consist of clauses in the “Treachery Act” (before 1934: “Treachery Decree”), which punish “hateful, inflammatory, or malicious remarks against senior figures of the state or the NSDAP”. Even statements of fact can now be punishable if the court considers their effect to be detrimental to the state. Thus, the claim circulated among the public that during the first boycott from 1 April 1933 patients in Hanover are being forcibly prevented from visiting Jewish doctors results in a 71-year-old Jewish woman being imprisoned for half a year. The Hanoverian NSDAP newspaper writes that “of course not a word of this gossip is true”. And yet these actions took place in the public eye – which was precisely their plan.

During the war, the incidence of “treachery trials” is outnumbered by trials against alleged “antisocial parasites”. But they continue to take place – with charges such as having doubts about the final victory, ridiculing “Nazi bosses”, showing compassion towards those persecuted. Remarks criticising the regime or telling so-called “whisper jokes”, which were anti-government jokes, carry a huge risk because of omnipresent informers. Examples of charges: because of claiming that people in other countries are freer than in Germany, “You can’t say what you think”, the Special Court of Hanover sentences a former Social Democrat to be committed to a mental hospital – thereby proving what he stated to be true. And because he regretted the failure of the assassination attempt on Hitler in the Munich Bürgerbräukeller in November 1939, the special court sentences two defendants to the draconian punishment of five years in prison each.

Wartime radicalisation

Directly as the war begins, numerous decrees are enacted “to safeguard home front security”, violation of which leads directly to trial in a special court. To ensure its propaganda maintains control, the Nazi regime makes eavesdropping on enemy broadcasters punishable by severe measures (Broadcasting Decree). Evoking a grim reminiscence of the hunger strikes in the First World War, a “War Economy Decree” regulates state control of economic life on all levels and the rationing of goods; offences such as failure to declare commodities, illicit slaughtering of animals, forging ration coupons such as food stamps, can all result in heavy prison sentences and even the death penalty. The same goes for previously minor offences such as petty theft if they were “committed by taking advantage of the special circumstances of the war”, i.e. during bomb alerts (“blackout crime”) or as a misdemeanour committed in burning houses or ruins (“looting”). The “Decree on Antisocial Parasites” is regularly invoked for this purpose.

In the second half of the war, men and women from the millions of forced labourers and prisoners of war, who literally slave away in the transport sector at the Reichsbahn [Imperial Railways] or Reichspost [Imperial Postal Service] and who are driven by constant hunger to open or steal (military post) parcels, often fall victim to it. In December 1943, Hanover Special Court sentences a French warehouseman to one year in prison for stealing two tins of fish. In October 1942, a Czech shunting worker is sentenced to 10 years in prison for stealing 40 parcels. Of the 210 known death sentences passed by the Special Court of Hanover (170 of which were carried out), 99 are handed down under the “Decree on Antisocial Parasites”.

Additional online information

Wikipedia entry: Special court

Wikipedia entry The repeal of Nazi unjust sentences [in German]

Wikipedia entry Enemy radio station

Wikipedia entry Law of Nazi Germany

Literature Click here

Texts and images: Michael Pechel

![Hanover behind the main railway station: Running vertically is Alte Celler Heerstrasse, with the court jail to the right of it and the courthouse buildings on the Raschplatz triangle. Photo album of the “Fliegerabteilung” [“Aviation Division”], ca. 1917. Historical Museum of Hanover](https://zukunft-heisst-erinnern.de/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/gerichtsgefängnis_4-1000x1000.jpg)