After the liberation from National Socialism, very few perpetrators from the top echelons of the Party, Gestapo, SS, industry and judiciary were punished. However, the repression and robbing of the Jewish population had many accomplices in public office and administrative departments: pen-pushing perpetrators. Terror and bureaucracy went hand in hand.

Expulsion was the aim

A main aim of National Socialist domestic policy is (initially) to drive all Jews out of Germany. Alongside overt terror, a raft of discriminatory laws and decrees causes half of the approximately 550,000 (1933) German Jews to emigrate abroad. Exodus waves follow hard on the heels of the extremes of the anti-Jewish measures, such as after the Night of Pogroms in November in 1938.

After the start of the war, it becomes virtually impossible to cross the German borders. As of October 1941, emigration is forbidden. Social and economic obliteration is now followed by physical death in the ghettos and extermination camps within occupied Eastern Europe.

Control of foreign exchange

In the years of the Great Depression, the Weimar Republic enacts strict regulations to prevent capital from being moved out of the country and to maintain the balance of trade. High capital taxes are levied on emigrants (“Reichsfluchtsteuer” = ‘Reich Flight Tax’). The Nazi state financial authorities adopt these restrictions, whilst increasing their severity so they become a primary means of robbing Jewish citizens of their assets.

In January 1939, a letter from the Foreign Ministry to the foreign consulates makes clear its intention “to drive the Jews beyond the borders as beggars”. Impoverished Jews are meant to be a burden on the country receiving them, with the aim of exporting German anti-Semitism. In practical terms, this contradicts the official objective of promoting emigration as it becomes increasingly impossible for Jews willing to leave to finance their escape or find a country willing to take them.

Legalised state robbery

Foreign exchange departments at tax and revenue offices, in collaboration with customs authorities, ensure that fleeing Jews leave behind as much of their property as possible. From December 1935, a change in the law on foreign exchange makes it possible to block the assets of anyone suspected of leaving the country – the owner is only allowed access to them if they get authorisation from a foreign exchange department. The amount of money allowed to be taken abroad steadily becomes less and less. Any credit balance remaining in Germany (emigrant’s assets) can only be transferred to the country of emigration after hefty deductions: forfeiture went up from 20 per cent in 1934 to 96 per cent in 1939. In this way, refugees become forced into bolstering German public finances, which have been ruined due to being geared to rearming for war.

Reduced to saving just their lives

Securing authorisation to take personal items is similarly restrictive and extortionate. As of 1938, only those household items that are absolutely necessary are allowed as personal effects that can be taken when moving out of a property. A charge equal to the original purchase price is levied on “new” goods, i.e. items purchased after 1933.

High taxes or an outright ban on taking the items with them is applied to anything that could possibly be turned into cash after fleeing: cameras, musical instruments, works of art or jewellery. It is forbidden to take any precious metals out the country. Financial authority documents from that time record in great detail how expropriation was carried out, even restricting how much underwear was permitted.

Sale of Jewish property

In autumn 1941, the remaining Jewish population in Hanover is forced to move into Jewish houses, dwellings specially designated for Jews. Tasks are divided up amongst different departments: evictions are coordinated by the city authorities. The Gestapo arranges the removal of property left in Jewish homes and transferring it to the city’s collection points. Tax officials turn Jewish property into money. Many “Volksgenosse” [a Nazi term denoting those of German blood] are able to benefit from this at public auctions.

Shortly after systematic deportations to the ghettos and extermination camps commence, a cynical law is passed on 25 November 1941: any German who transfers their habitual abode to a country other than Germany automatically loses their citizenship and all assets shall be forfeited to the State. Before they were expelled, those affected were obliged to hand over detailed lists of their possessions to the Gestapo. The ensuing sale of effects for the benefit of the public purse also falls in the domain of the financial authorities: from the end of 1941, administering and selling the possessions of deported Jews is the responsibility of the ‘Offices for the Disposal of the Property of Jewish Emigrants’ run by the State Tax Offices in close cooperation with the Gestapo.

The financial bureaucracy performed the same role in the persecution and robbing of the Sinti, which was similarly racially motivated.

Foreign exchange department

The prestigious building in Hardenbergstrasse 3-4 was constructed in 1905 for the Prussian Directorate General of Customs in Hanover. From 1919, it serves as the headquarters of the Hanover Regional Tax Office [= Landesfinanzamt Hannover, after 1937 known as the “Oberfinanzpräsidium Hannover, the State Tax Office”]. Until 1937 and from 1943 to 1945, the foreign exchange department is also housed here. Between 1937 and 1943, the foreign exchange department operates in the building at Waterlooplatz 11 next to the Hannover-Waterlooplatz tax office, both in former Guelph barracks. The Asset Reclamation Office [Vermögensverwertungsstelle], founded at the end of 1941 at the same time as the first wave of deportations, is also located at the same address.

Up until 2002, a general embargo of 80 years still applied to tax records. It was only when archive law was changed that the files held by the Regional Finance Office [“Oberfinanzdirektion”] from the time prior to 1945 were able to be handed over to the main state archive. This made them available for historians to study, whereupon they revealed the true extent to which the tax authorities were complicit in Nazi politics.

Additional online information

Claus Füllberg-Stolberg The role of the tax authorities in the expulsion of the Jews: The Seligmann family from Ronnenberg near Hanover [in German]

Hans-Dieter Schmid “…how to deal with Jewish matters”. The treatment of the Sinti and Roma by the financial authorities [in German]

HAZ 08.04.2011 New study: Finance officials helped in Hanover in the persecution of Jews [article in German]

Wikipedia entry Foreign Exchange Department [in German]

Further reading: Click here

Texts and images: Michael Pechel

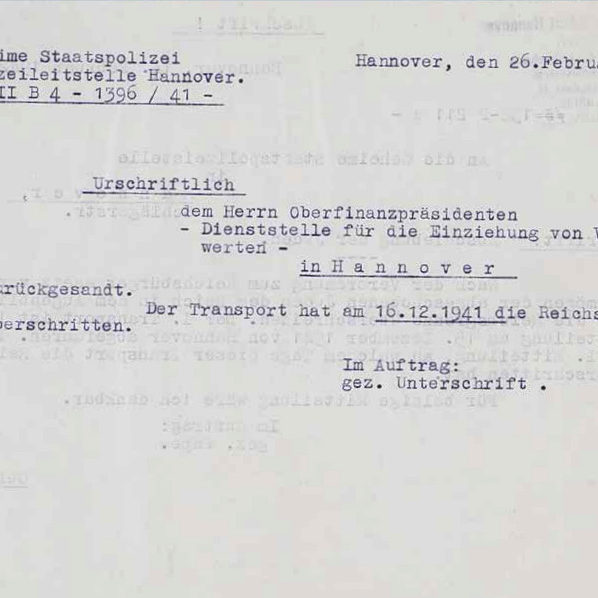

![Hanover: Question from the Chief Finance president to the Secret State Police headquarters dated 14.02.1942, asking when the transportation [of Jews] to the Riga Ghetto crossed the German border. Lower Saxony State Archives Hanover Hann. 210 Acc. 2002/141 No. 8. The archive material is the property of the Lower Saxony State Archives. This image may not be stored, reproduced, archived, duplicated, copied, altered or used in any other way without the prior written consent of the Lower Saxony State Archives.](https://zukunft-heisst-erinnern.de/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/oberfinanzpraesidium_1.1-597x597.jpg)