Four scale models of the city vividly illustrate Hanover’s development, from the time it was the small residential seat of the House of Guelph (or Welf) (1689), to an industrial city on the eve of the Second World War (1939); then from the almost completely destroyed city centre (1945) to its transformation into a “car-friendly city” (2012).

Princely seat of the House of Guelph

The Guelph sovereigns made Hanover their capital and residence in the middle of the 17th century. The oldest model shows Hanover as a stronghold fortified by bastions and moats with the princely palace located on the upper bank [am Hohen Ufer] of the River Leine – today the seat of Lower Saxony’s State Parliament [Landtag]. Set between the Marktkirche and the Kreuzkirche – two of the churches in the Altstadt – the “Ballhof” near the palace is used by court society as a place for events and entertainment, ball games, theatrical performances and concerts. The city is divided into the Altstadt [Old Town, i.e. the historic centre] and Neustadt [New Town] by the course of the River Leine.

Religious tolerance

Since the time of the Reformation, the Council of the Altstadt has imposed strict Lutheran rule and expelled followers of other confessions (Catholics, Jews, Reformed Christians), however in the Neustadt of the Principality of Calenberg greater religious freedom was enjoyed. The street Rote Reihe represents a “Mile of Tolerance” with churches of the Reformed Church, Catholics and, as of 1703, a Jewish synagogue.

A modern industrial city

In the model from 1939, only the maze of alleyways in the Altstadt evoke Hanover’s mediaeval origins. Since the 19th century, Hanover has developed into an industrial city with half a million inhabitants located at an important railway junction. It is home to key companies in the metalworking (e.g. Hanomag, Eisenwerke Wülfel), food and beverage (e.g. Sprengel, Bahlsen, Appel-Feinkost), chemical (e.g. Pelikan, Continental), textile (e.g. Lindener Samt [velvet producers], Döhrener Wollkämmerei [wool combing plant]), electrical engineering and communication (e.g. Deutsche Grammophon, Hackethal Draht- und Kabelwerke [wire and cable manufacturers]) industries.

Industrialisation produced a strong, social democratic-inspired workers’ movement with its centres in the districts of Linden, Wülfel, Döhren and Oberricklingen – the large trade union building at Goseriede is a symbol of its power. In the years from 1918 to 1924, Hanover’s first democratically elected Oberbürgermeister [lord mayor] was a Social Democrat.

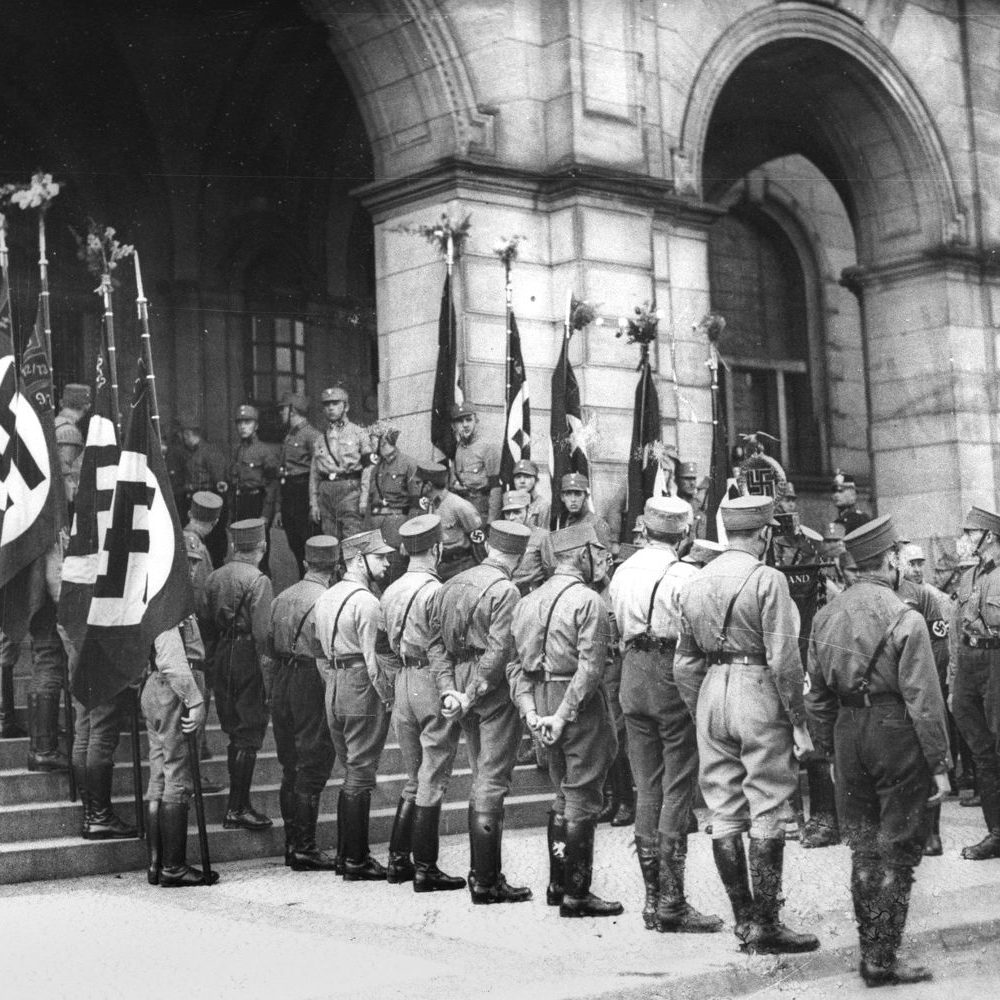

Victory for the swastika

However, the model from 1939 shows a Hanover under the sway of the National Socialists. Up until the end of the 1920s, the NSDAP [Nationalsozialistische Deutsche Arbeiterpartei, i.e. National Socialist German Workers’ Party or Nazi Party] is a right-wing fringe party. In the city elections in 1929, the NSDAP gains just 4.9% of the votes and the SPD [Sozialdemokratische Partei Deutschlands, i.e. Social Democratic Party of Germany] 48.6%. Yet shortly afterwards, in the shadow cast by the world economic crisis, the Party achieves outstanding successes. In the last relatively free city elections in the middle of March 1933 – already after Hitler had been appointed Reich Chancellor – the Nazis secure 42% of the votes in Hanover. Nevertheless, 32% still go to the Social Democrats. However, repression of the left and “Gleichschaltung” [enforcing political conformity through alignment with Nazi ideology] of the middle-class parties, which went uncontested, ensures a swift victory for the swastika in Hanover’s New Town Hall.

Economic boom driven by re-arming for war

For Hanover, too, 1939 marks the start of the Second World War, precipitated by the National Socialists’ invasion of Poland. Companies have long since switched to a war economy, thereby creating artificial economic prosperity with full employment. From 1933 to 1938, production at Continental tyre factory – Hanover’s largest corporation – increases fourfold and its workforce doubles. And by 1936, Hanomag in Linden – which instead of cars and locomotives now manufactures guns, submarines and tracked-vehicles – has quadrupled its workforce in the space of three years.

The symbolism of the Synagogue

It is a different story for Jewish businesses. These come under pressure from calls for boycotts and discriminatory tax treatment and are frequently forced to close their operations. From January 1939, a decree forbids Jews for good from operating businesses, working in trades and commerce, or providing services. The National Socialists’ aim of driving them out of Germany is also successful in Hanover: by the outbreak of war, more than half of the Jewish population has fled abroad to escape harassment and deprivation of their rights, leaving behind an ageing community of barely 2,000 people.

The model contains a deliberate historical inaccuracy: the New Synagogue in Calenberger Neustadt had already been destroyed by arson during the “Night of Pogroms” in November 1938 and demolished shortly afterwards. It is shown here as a symbol to mark its rightful place in the urban landscape.

The end result: a city in ruins

Within the space of a few years, the ravages unleashed by the National Socialists rebound on the whole of Germany. By the end of the war, after 88 air raids, bombs have all but totally annihilated Hanover’s city centre. Ninety-nine per cent of all buildings in the inner city are destroyed. Half of the dwellings in Hanover are uninhabitable. Among the churches in the Altstadt that were destroyed is the Aegidienkirche. It has deliberately not been rebuilt: since 1954 its burnt-out shell in the heart of the city has served as a key memorial symbolising peace in Hanover.

DP: Displaced Persons

When American soldiers march into Hanover on 10 April 1945, they liberate around 42,000 displaced persons: civilian forced workers, prisoners of war and concentration camp inmates. In Hanover, as in the rest of Germany, deportees from all the Nazi-occupied countries had to keep the war economy going. When the war ends, almost one in five inhabitants is in the city as a result of forced labour. The fate of these Displaced Persons (“DPs”) is documented in the “Grotte”, a memorial space a few metres away from the models of the city at the entrance to the “Gartensaal” restaurant.

Reconstruction? New construction!

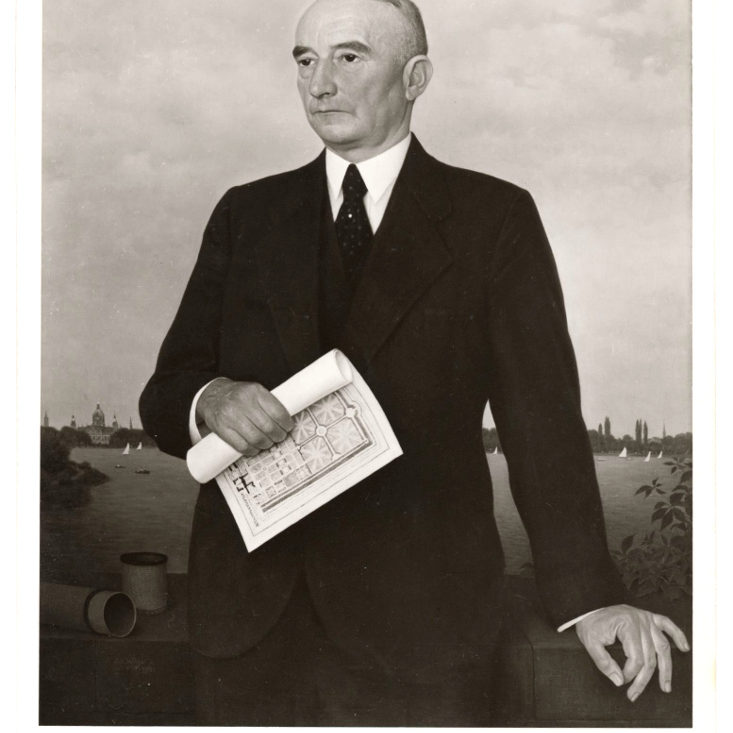

Hanover city centre is rebuilt remarkably quickly. As City Planning Director from 1948 to 1975, the architect and town planner Rudolf Hillebrecht plays a key role in this transformation. He anticipates the rise of private transport on the lines of the American model and tailors his planning approach accordingly: a system of urban motorways and wide highways is designed to direct car traffic around the inner city, whilst at the same time giving easy car access to all central shopping areas. In the 1950s, this was considered ground-breaking: urban planners from all over Germany flock to the Leine. In 1959, Der Spiegel [influential weekly current affairs magazine] dedicates a lengthy cover-feature profiling Hillebrecht under the headline title “Das Wunder von Hannover” [“The Hannover Miracle”].

These days, the car-focused thoroughfares cutting through the city are viewed with criticism. Many buildings that had survived the war had to be demolished to make way for these new roads. While Hillebrecht advocated the reconstruction of certain city-centre public buildings (the Opera House, Palace, Wangenheimpalais…), he considered the architecture from the turn of the century (the “Gründerzeit”, [literally “founders’ period”, architecturally the period from 1850 to 1914]) to be devoid of style and without merit. His critics accuse him of bringing about the “second destruction” of Hanover.

Additional online information

Wikipedia entry Rudolf Hillebrecht

Wikipedia entry History of the City of Hanover [timeline in English, more detail in German]

hannover.de History of Hanover in figures [in German]

Further reading: Click here

Texts and images: Michael Pechel

![View from the dome of the New Town Hall towards Leineschloss [former Princely Palace]. On the left, the dome of the New Synagogue in Calenberger Neustadt can be seen, so the photo was taken before November 1938. Source: HRC](https://zukunft-heisst-erinnern.de/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/Blick_Rathauskuppel-1180x1180.jpg)

![Hanover: Inauguration of the civic leaders on 6 April 1933 in the hall beneath the dome of the New Town Hall. From an article in the Lower Saxony Daily Newspaper [NTZ] of 8 April 1933. Historical Museum of Hanover](https://zukunft-heisst-erinnern.de/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/Neues_Rathaus_1933-972x972.jpg)

![Hanover 17 November 2015: “LICHTzeichen: Hannover – ein Mehr aus Licht [a Greater Light].” In commemoration of the terrorist attacks of 13 November 2015 in Paris, the city’s New Town Hall was illuminated in the colours of the French Tricolour Wikimedia Commons. Photo: Bernd Schwabe in the Wikipedia office in Hannover](https://zukunft-heisst-erinnern.de/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/Neues_Rathaus_10-1000x1000.jpg)