At the end of the 19th century, a community centre was established on the edge of Calenberger Neustadt, which offered teacher training, a boarding school, a day nursery for children and a religious school. After the Second World War, the buildings become the most important place of refuge for Jewish Displaced Persons.

How it all began

It starts with Moritz Simon (1837-1905) and his vision of sparking a tradition of following practical trades and agriculture through educating Jewish children. In 1884, this Jewish banker from Hanover founds the “Society for the Promotion of Instruction in Horticulture and Manual Skills in Jewish Schools” [Verein zur Förderung des Gartenbau- und Handfertigungsunterrichts in Jüdischen Volksschulen] and donates a plot of land on Ohestrasse. It is here that, in 1892, a Jewish teacher training college is established with an adjacent area for horticultural classes. Instruction in pasteboard work and woodwork takes place in the basement of the building. However, Simon is apparently not content just to stay with the combination of teacher training and classes in manual skills. In the same year, he buys a much larger plot of land on the outskirts of Ahlem village, near Hanover, where he founds the Israelite School of Horticulture Ahlem.

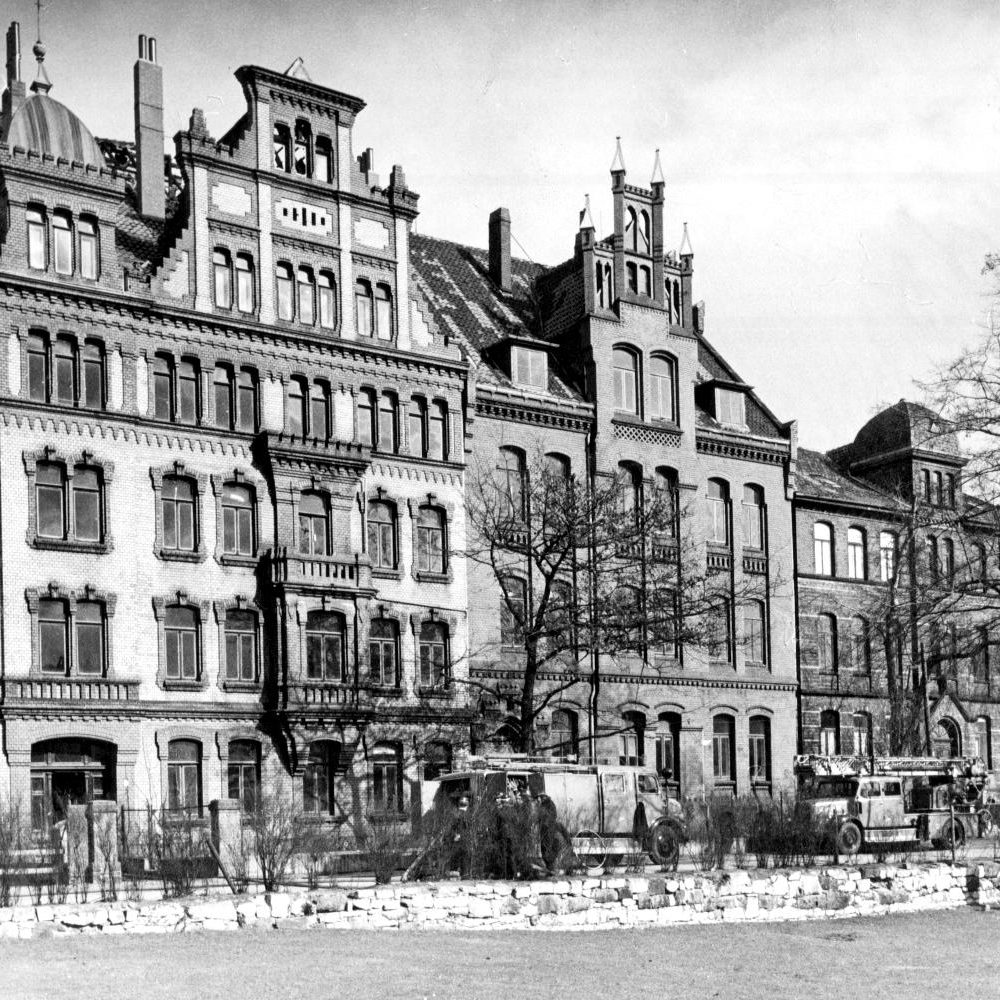

The teacher training college exists here until its closure in 1921. It comprises the original teachers’ seminary, which offers a five-year training programme in the building at Ohestrasse 8; a boarding facility to accommodate the students in the adjacent building at Ohestrasse 10; and a school for teaching practice, which, prior to 1935, was the only public Jewish school in Hanover.

Other functions

In 1913, the “Alexander and Fanny Simon Foundation” [Alexander und Fanny Simon‘sche Stiftung] builds a kindergarten and crèche at Ohestrasse 9, on the section of the garden set back from the street. It is designed by the renowned architect Heinrich Tessenow (1876-1950), who has previously undertaken work for the Foundation (apprentice hostel for the school farm for training young Jewish farmers in Steinhorst near Celle, and the teacher training college in Peine). In keeping with the spirit of Moritz Simon, who dedicated the charitable foundation to the memory of his parents, the kindergarten also includes gardens and workshops.

The teacher training seminary ceases its activities at the end of the school year 1921. This is due to the First World War and the ensuing drop in the value of money: firstly, the number of teachers in training fell sharply, and secondly, the school’s governing body experienced a sudden and drastic loss of capital. The Jewish community of Hanover becomes the legal successor to its assets. The community had already been using the building at Ohestrasse 8 as its second religious school (in addition to the religious school in Lützowstrasse) for some time. Other facilities, such as offices and the makeshift kitchen for the synagogue community, are now added. Later, the entire “Central Office for Welfare in the Hanover Synagogue Community” [Zentralstelle für Wohlfahrtspflege in der Synagogengemeinde Hannovers] moves into the building. Since 1909, it has been responsible for coordinating the work of more than 20 charitable Jewish associations and foundations.

During the dictatorship

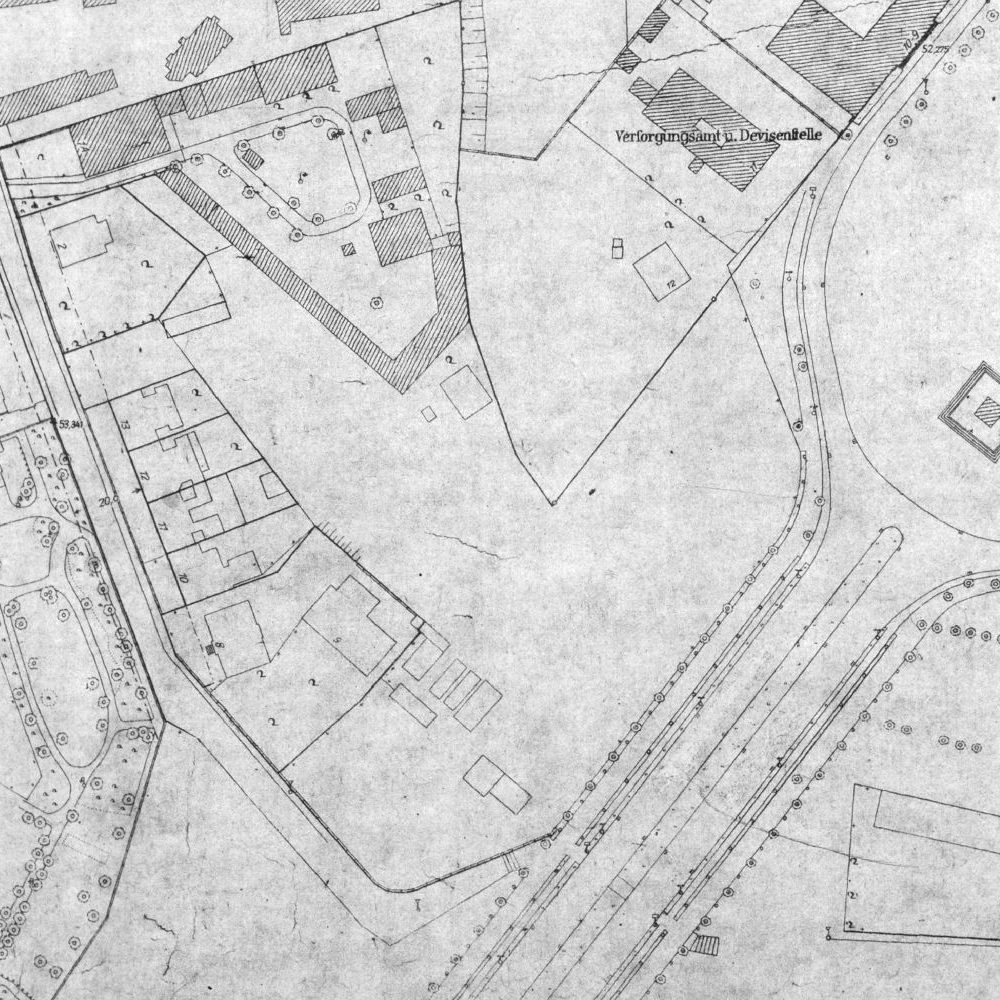

The plans for redesigning Hanover as a “Führer City” [status given to certain German cities by Hitler based on his vision of gigantic urban transformation projects] also extend to Waterlooplatz and its surroundings. The idea is to construct one of three forums here: the “Government Buildings Forum” (see Maschsee). However, the buildings on Ohestrasse stand directly in the way of achieving this. On 7 November 1938 (two days before the night of pogroms!), the city authorities notify the Jewish community of their interest in the properties at Ohestrasse 8 and 9. Negotiations drag on. Finally, 1 July 1942 is agreed on as the date for the transfer of ownership. But before that, two things happen: the protection of tenants’ rights for Jews is abolished, causing increasing numbers of them to move into the community centre on Lützowstrasse; in turn, this forces the Jewish school in April 1940 to relocate from there into the community centre on Ohestrasse as it is bigger; classes continue here until the beginning of September 1941 – this is until these buildings, the same as a total of 15 privately or publicly owned Jewish houses in Hanover, are designated as “Jewish houses” by the city authorities. They are then used to accommodate Jews prior to them being deported. From 3 September 1941 until the first transport to Riga on 15 December 1941, about 200 of the 1600 Jews still living in Hanover are forced to live in these two buildings. Once this deportation has taken place, the numbers drop abruptly to about 25, until they are replaced by people from other “Jewish houses” that are being closed.

On 1 July 1942 – the day of the agreed handover and after the large-scale transports of Hanoverian Jews to Riga and the Warsaw Ghetto – both buildings stand empty. They are put to use for purposes relating to the war: a group of French prisoners of war moves into the former day nursery, whilst the front building at Ohestrasse 8 is occupied by the guard detachment assigned to them, the city’s war property damage office, and also tenants coercively selected by the city authorities. In his memoirs, Fritz Treu, a Jew in a “mixed marriage” and, prior to 1933, a member of the “Sozialistische Arbeiterpartei Deutschlands” (SAP) [Socialist Workers’ Party of Germany], reports how, as a forced labourer of a construction company, he had to accompany French prisoners of war from Ohestrasse to the building site of a bunker every day – revisiting the former Jewish religious school where as a child, most probably reluctantly, he learned Hebrew.

Displaced Persons

On 10 April 1945, American troops liberate more than 40,000 prisoners of war, forced labourers and concentration camp survivors in Hanover. Under Allied protection, all non-Germans receive the status of Displaced Persons (DPs). Many of them are of Jewish descent. Whereas the relatives of Western European countries are repatriated very quickly, the Eastern European Jewish survivors of the Holocaust have to wait for years in limbo in the country of their persecutors. This only changes when immigration regulations, in particular to the USA, are relaxed and the State of Israel is founded.

With at times more than 1200 members, the Jewish DP community in Hanover is the largest in the British zone after Bergen-Belsen. They organise themselves into the ” Jewish Committee”, separate from the newly emerging German Jewish community, to represent the interests of the “Sh’erit ha-Pletah” (“surviving remnants”). They base themselves in a former administration building in Vinnhorst, the kibbutz on the grounds of the former Israelite School of Horticulture Ahlem, and also at the former Ohestrasse community centre. The main languages of communication are Yiddish and Polish. Many of the residents are survivors of the concentration camps in Ahlem or Bergen-Belsen. Because it is located in the city centre and is also a hub for distributing aid, Ohestrasse takes on an important role.

Ohestrasse: The nerve centre of (eastern European) Jewish life

The Jewish Committee of Hanover is founded in the summer of 1945 in the houses at Ohestrasse 8/9. The exact date is not known; Jewish survivors have presumably been living illegally in the buildings for some time. It is not until November 1945 that they are commandeered by the British authorities for use as an “Assembly Centre”. It is here that the committee’s administrative offices are set up, new arrivals are registered, missing persons lists for relatives are posted, and relief supplies from Jewish aid organisations are distributed. Like all DP camps, the site was officially under the authority of the United Nations Relief and Rehabilitation Administration (UNRRA) until the end of 1946, and then under the authority of the UN’s International Refugee Organisation [founded in 1946 to deal with the massive refugee problem created by World War II]. In 1946, the UNRRA team lists between 140 and 195 permanent residents. Eyewitnesses describe a total of more than 20 dormitories in the two houses, each of which has to be shared by seven to eight people. Added to this, there are washrooms, rooms for clubs and meetings, an area for sports, the infirmary, a synagogue, rooms for schooling and vocational training, a tailor’s workshop, and so on. In the summer of 1946, basic training workshops are organised outside in corrugated iron huts: a register from May 1947 kept by the Jewish aid organisation ORT (Organisation – Reconstruction – Training) shows 24 students learning about car mechanics, 12 training to become electricians and 16 being trained in welding in Ohestrasse.

Not only that, Ohestrasse is also the main meeting place for the large number of non-German Jews who, in their desire to attain autonomy as “free-living Jews”, have sought their own place to live in the city – yet constantly in fear that by doing so they will lose their status as DPs. By the end of 1945, this number has risen to around 900 people. In Jewish centres like Ohestrasse, they seek social connection and a common culture There is a request for an orchestra, a library is set up, in the halls of the Jewish restaurant in Ohestrasse, performances put on by the Bergen-Belsen Concentration Camp Theatre are staged. But Ohestrasse is also literally a focal point for political conflicts: following a public speech made by the British Foreign Secretary about what he called the “Jewish problem” in Palestine, protests also erupt in Hanover. In the courtyard of Ohestrasse on 16 November 1945, hundreds of people with blue and white armbands gather beneath banners bearing demands such as: “We Want the Gates of Palestine Opened”. British military police use force to break up the demonstration, its leaders are arrested, which results in the trial of five men and three women, culminating in prison sentences. The incident is covered in the media stretching all the way to the USA.

The end

In contrast to the German-Jewish community, the members of the Jewish Committee regard themselves from the outset, with few exceptions, as a community on standby waiting to be called: the aim is to emigrate to a host country (preferably) located outside of Europe. After 1948, membership numbers fall drastically from 1100 to 250 (1949).

In May 1949, the buildings at Ohestrasse 8/9 are vacated by the British occupying forces and shortly afterwards made available to the city’s land registry office. The city wants to keep ownership of it just in case, as there is a plan to widen Ohestrasse to make it into a connecting road as part of Hillebrecht’s traffic scheme. Instead, in the end they build Gustav-Bratke-Allee. When the vocational training centres are built in the 1950s, Ohestrasse becomes a cul-de-sac and in 1970 its historic buildings fall victim to the demolition excavator.

In April 1990, a memorial was inaugurated at the former site of the teacher training seminary to commemorate Jewish life in Ohestrasse. Students from the local vocational training centre play a major role in designing it.

Additional online information

Wikipedia entry Memorial to Jewish life in Ohestrasse [in German]

Wikipedia entry History of the Jews in Hannover

Wikipedia entry Vocational training centre (Hanover) [in German]

Further reading: Click here

Texts and images: Michael Pechel

![Hanover: Israelite day nursery, Ohestrasse 9, 1913-1914. Commissioned by the Alexander and Fanny Simon Foundation of Hanover. Designed by Heinrich Tessenow. Photo from: Marco De Michelis, Heinrich Tessenow 1876-1950. Das architektonische Gesamtwerk [The Complete Works of Architecture]. Stuttgart 1991](https://zukunft-heisst-erinnern.de/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/Ohestr_9-738x738.jpg)