You are currently viewing a placeholder content from Default. To access the actual content, click the button below. Please note that doing so will share data with third-party providers.

More InformationJewish life in Hanover

The inauguration of their first dedicated synagogue in 1870 marked the moment when the Jews of Hanover felt they had been accepted into society. Barely seventy years later, this promise of equality was retracted by the National Socialists and the site of the New Synagogue stood empty.

From the ZeitZentrum Zivilcourage the route leads down Friedrichswall to Friederikenplatz. Turning left between the historic Lower Saxony State Archives and going past the Reformed Church, we then enter what was formerly royal Calenberger Neustadt. Along the “Mile of Tolerance” once stood the Reformed Church, the Protestant Church of the Court and the City, the Jewish Synagogue and the Catholic Church of St. Clemens – an example of the religious tolerance of the House of Guelph.

In Archivstrasse we turn the corner, going through the “Haus kirchlicher Dienste” and into Wagenerstrasse. In front of what used to be house number 1, a Stolperstein commemorates Hermann Federmann who was a young Jewish victim of Nazi euthanasia. Continuing on “Rote Reihe”, we arrive at the former site of the Neue Synagoge, inaugurated in 1870, where there is a small memorial and an information panel. On the night of the pogroms from 9 to 10 November 1938, it was set on fire by the National Socialists and later blown up.

Cross the River Leine by walking over Martin-Neuffer-Brücke to reach Am Hohen Ufer, the oldest part of Hanover. Here, you can either follow the main route to the right or turn left to make a quick looping detour up to Goethestrasse to take a look down Lützowstrasse and the site of the former Jewish Community House. This was designed in 1875 – not long after the Neue Synagoge had been built – by the well-known Jewish architect Edwin Oppler. Today, a somewhat mundane multi-storey car park stands on the site of the building that burnt down in 1943. Continuing along Scholvinstrasse (caution: red light district!) – passing the Stolpersteine for the Jewish baker’s family Bloch – you arrive back on the main route at Am Hohen Ufer.

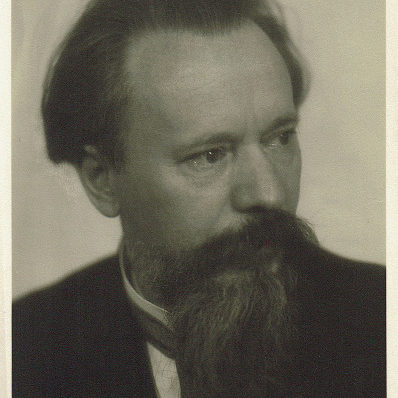

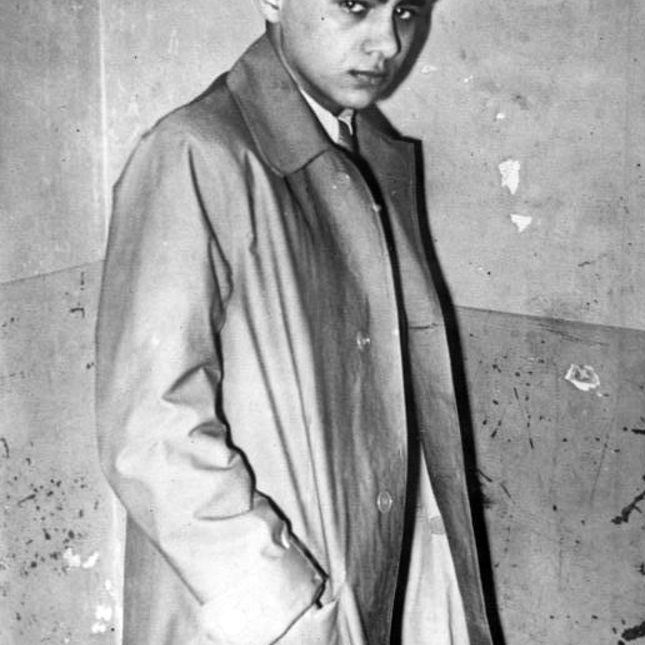

Where the Ada and Theodor Lessing Volkshochschule [adult education centre] now has its main site, there once stood the “Rusthaus”, named after the NSDAP Gauleiter Bernhard Rust, until it was destroyed in 1943. In October 1938, almost 500 Jews of Polish nationality were detained in the ceremonial hall here before being deported: a prelude to the November pogrom. A commemorative plaque and Stolpersteine in front of the “Historisches Museum Hannover” are a memory to Herschel Grünspan (also written Grynszpan) and his sister Esther. The shots fired by the 17-year-old Jew at a German diplomat in Paris provided the National Socialists with their pretext for the violent pogrom of November 1938.

Neighbouring Kramerstrasse still boasts a few half-timbered houses, which survived the bombing in the war. In front of house number 19/20, there are Stolpersteine for the members of the Eigermann family. They were a large family who, like the Grünspans, were Jews who had immigrated from Eastern Europe and who were forcibly deported from Germany in October 1938.

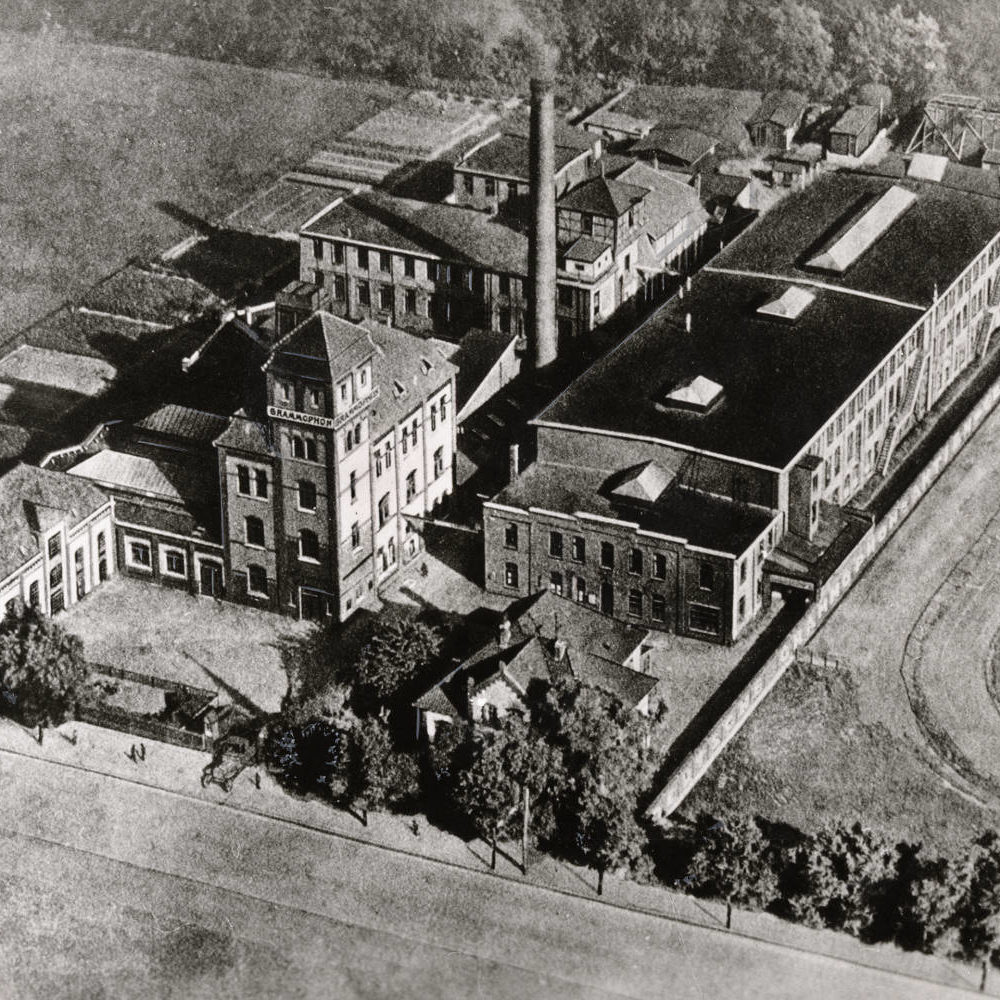

Continuing past the market square, crossing over Schmiedestrasse, then going down Seilwinderstrasse, you come to the junction of Seilwinderstrasse, Osterstrasse and Grosse Packhofstrasse. To the left and right here stood the illustrious department stores of Hanover. Four of them were Jewish-owned: after they were placed on a legally equal footing in the second half of the 19th century, Jewish entrepreneurs played an important role in Hanover’s development.

Stroll across the “Platz der Weltausstellung”, then turn into Ständehausstrasse. This will bring you to the Opernplatz. The Holocaust Memorial you see here in this prominent location was erected in 1994 and yet it had to be fought for by a civic initiative, which had met with resistance expressed in letters-to-the-editor columns. More than 1,900 names inscribed on the stone panels commemorate the deportation and murder of Hanover’s Jewish citizens. A plaque tells their story and how the monument came into being.

On the other side of Georgstrasse, the Jewish Steinitz family lived on the elegant first storey [USA: second storey] of the historic Haus Basse. During the 1920s, Käte Steinitz was at the heart of Hanover’s Modernist scene, both for art and literature. Her salon was a meeting place for the avant-garde – until the National Socialists put an end to this.

The route wends its way past the landmark memorial to the victims of war and violence, manifested in the ruins of the Aegidienkirche, and back to the ZeitZentrum Zivilcourage.

![Hanover: Jewish Community House in Lützowstrasse 3, street-facing front. Architectural drawing from: Peter Eilitz: Leben und Werk des königl. hannoverschen Baurats Edwin Oppler [Life and Work of the Royal Hanoverian Architect Edwin Oppler]. In: Hannoversche Geschichtsblätter. New edition, Volume 25, 1971](https://zukunft-heisst-erinnern.de/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/gemeindehaus_vorderfront-527x527.jpg)

![Hanover: Haus Basse, the bank in Georgstrasse (on the left behind the car), Käte Steinitz's salon was on the elegant first storey [USA: second storey]. Behind it was the press building built in 1927 for the "Hannoverscher Kurier". The National Socialist "Niedersächsische Tageszeitung" ["Lower Saxony Daily Newspaper"], the NTZ, moved in here in July 1934. Photo by Wilhelm Hauschild, 1937. Hauschild Archive in the Historical Museum of Hanover](https://zukunft-heisst-erinnern.de/wp-content/uploads/2020/01/J_Steinitz_1-1-1000x1000.jpg)

![Hanover: Page from the children's book by Kurt Schwitters, Käte Steinitz and Theo van Doesburg (typographic design), “Die Scheuche” [“The Scarecrow”], fairy tale, 12 pages printed in blue and red, 1925. Kurt Schwitters Archive in the Sprengel Museum Hanover](https://zukunft-heisst-erinnern.de/wp-content/uploads/2020/01/J_Steinitz_6-1000x1000.jpeg)